Taxonomy

Assessment Information

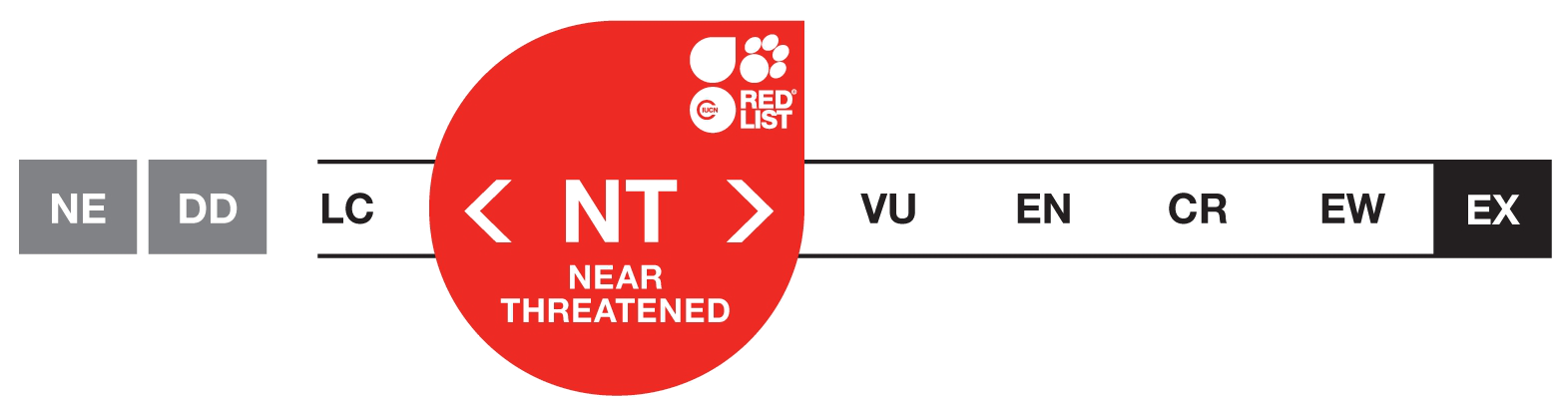

- IUCN Red List Category and Criteria

- Near Threatened A2bcde ver 3.1

- Assessment language

- English

- Year published

- 2020

- Date assessed

- 2020-01-30 00:00:00 UTC

Geographic Range

In China, Himalayan Tahr was discovered in 1974 in Quxiang of Buoqu Valley (aka Zhangmu Valley) in southern Tibet (Beijing Natural History Museum and Qinghai Institute of Biology 1977). Since then, there has been no additional information pertaining to its occurrence or status. A confirmed report of species presence came from Tibet’s Geelong-Buoqu Valleys (Wang et al. 1984, Feng et al. 1986, Wang 1998, Smith et al. 2008, Hu et al. 2014) and Qomolangma Nature Reserve (pers. comm., Labaciren) where numbers of tahr have been sighted regularly in the Rongxia and Chentang valleys.

In India, Himalayan Tahr occurs along subalpine regions across southern forested slopes in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Sikkim (Sathyakmuar 2002). Populations are patchily distributed from south-central Kashmir through the southern part of Kullu (Himachal Pradesh) between c. 2,000 and 3,300 m (Gaston et al. 1981, 1983). They are widely present at similar elevations from northern Uttarakhand all the way to the border of Nepal. Small numbers of tahr also inhabit east Sikkim (nearby India-Nepal border) and west Sikkim (close to India-Bhutan border).

In Nepal, Himalayan Tahr formerly had a continuous distribution between 1,500 m and 5,200 m, but this has been increasingly disrupted by human activities such as livestock-grazing and subsistence hunting (Green 1978, 1979, Ale, S. B. unpubl. data). Overall, in Nepal, tahr inhabits temperate to sub-alpine forests and alpine meadows, mainly between ca 2,500 m and 4,000 m, but individuals at times venture up to 5,200 m. Schaller (1977) mapped fourteen locations of tahr in Nepal, but there are undoubtedly more.

In Bhutan, tahr is reported from the Jigme Khesar Strict Nature Reserve (Tshewang et al. 2018). However, Bhutan Government’s Nature Conservation Division of the Department of Forest and Park Services has not confirmed its presence in the country (Sonam Wangdi, December 2019, pers. comm.).

Population

No global population estimate of Himalayan Tahr is currently available. The rate of its population change is unknown.

Only a few Himalayan Tahr have been observed in China (Feng et al. 1986). Perhaps, between 400 and 500 tahr, all located in southern Tibet, may exist in China (Wang 1998).

No estimate of tahr population in India is available, however, a number of sporadic counts of tahr are available from across the range. In Himachal Pradesh, for instance, approximately 130 in Kanawar Wildlife Sanctuary, and over 100 in Great Himalayan National Park (S. Pandey, pers. comm.) were reported. Population estimates have also been reported from parts of Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary: 70 in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (Sathyakumar 1994), and 110 in the Tungnath region of Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (Kittur et al. 2006). One survey between 1996 and 1998 indicated 50 tahr inhabiting Tirthan valley of the Great Himalayan National Park (Vinod and Sathyakumar 1999). Kandpal and Sathyakumar (2010) reported tahr from the Pindari glacier area. A recent high altitude ungulate survey in 2016 estimated 297 tahr (range: 222–565, 0.32 animals/sq. km) from Uttarakhand (Habib et al. 2016).

A number of anecdotal evidences suggest several local extinctions of tahr in India (Sathyakumar, S., unpubl. data). They may be close to extirpation from western parts of Jammu and Kashmir. The entire population reported earlier from north of the Chenab River (between Kisthwar and the Banihal pass) is believed to be locally extinct now. Small populations of tahr survive in Bani-Sarthal (Kathua) and Kisthwar National Park (Kisthwar-Doda) (Bhatnagar et al. 2007). Density estimates ranging from as high as 19.6 to 25.7 per km² (Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary, Uttarakhand) (Sathyakumar 1994) and from as low as 1.4 to 4.6 per km² (Great Himalayan National Park, Himachal Pradesh) (Vinod and Sathyakumar 1999) have been reported from different parts of Western Himalaya.

A different abundance index, that is, encounter rates (number/km walked) indicated tahr was less abundant in Nanda Devi National Park than Tungnath in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary (Sathyakumar 1993, 1994). Also, the tahr population was denser in Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuary than Great Himalayan National Park (Vinod and Sathyakumar 1999). A camera trap survey (trap nights/100 days) from the upper catchment of Bhagirathi River revealed higher abundance of tahr in temperate habitat (4.4 ± 2.62) than alpine habitat (0.6 ± 0.34) (Pal et al., in press). In Sikkim, an intensive study in Prek Chu Catchment found the presence of Himalayan Tahr in subalpine and alpine zone, but they were rare compared to other ungulates such as blue sheep (Bhattacharya 2013).

No total population size estimates of tahr are available for Nepal, but there have been several sporadic surveys from different parts of the country over the decades. Bauer (1988) estimated 1,000 tahr for Sagamartha, Makalu-Barun and Langtang National Parks. These three regions obviously support more tahr than Bauer’s estimates, as revealed by relatively recent studies (see below).

Sagarmatha (Everest) National Park can easily support 700-800 tahr, at least half of them occurring in Namche, Phorste, Thame and Gokyo valleys, in an area of ca 160 km². The overall mean group size was 8.5, from 2004 to 2006, with an overall density of 3.4/km2 (Lovari et al. 2009, Ale 2007). Between 1989 and 2010, there was a decrease of tahr by some 2/3, from ca 350 to ca 100 tahr, in the core area of Sagarmatha National Park because of increased predation following the return of the snow leopard (Lovari & Mishra 2016). The recent data are lacking but numbers of predator and prey may have estabilised by now in Everest (Sandro Lovari, pers. comm.).

The most recent survey, in 2012, revealed a minimum of 394 tahr from Langtang in ca. 79.3 km² (density 5.3 tahr/km²: Thapa 2012). Green’s (1978) density estimates in Langtang National Park were similar in some localities (6.8 per sq. km) but in other localities they reached as high as s 25.0 per square kilometre.

Tahr has been reported from all of Nepal’s mountain protected areas but there have been no systematic surveys in these parks. No data on tahr are available from Gaurishankar Conservation Area, but in 2010 a short survey on the status of snow leopards also revealed the presence of tahr in Rolwaling valley in Gaurishankar. Their numbers, however, were dwindling (just 12 individuals observed, although with a decent kid-to-female ratio of 0.7: Ale et al. 2010). A recent survey (Devkota et al. 2017) in an area of 124.2 km2 in the upper reaches of Tsum valley, in Manaslu Conservation Area, revealed 223 tahr (nine herds, average group size of 25, range 2 to 74 individuals; a density of 1.8 animals per km2). Earlier in 2012, just two-day observations yielded at least 400 in the Tsum Valley and a similar number from the Budhi Gandhaki Valley in Manaslu (Sandro Lovari and Madhu Chettri, unpubl. data). The recent status of tahr in Annapurna Conservation Area is lacking but Gurung (1995) counted over 500 tahr in Annapurna Base Camp (density of 7.7/km2).

A total of 285 tahr were reported from Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve by Kandel et al. (2011). Tahr has been sighted in Shey Phoksundo, Khaptad, and Rara National Parks, in western Nepal. Even though there have been no formal surveys, each of these parks were reported to support at least 50 tahr, according to local experts (quoted in Gurung, 1995). Many districts that fall outside of protected areas, such as Dolpo, Jumla, Humla and Jajarkot, have been reported to contain sparse populations of tahr (Raju Acharya, Karan B. Shah, pers. comm.).

A number of anecdotal evidences suggest that considerable local extinctions of tahr have taken place in Nepal. Overall, conservative estimates of tahr population for entire Nepal may not exceed 10,000 (Som B. Ale, unpubl. data).

The potential habitat of Himalayan Tahr, worldwide, between 2,200 m and 4,200 m elevation, is estimated at c. 44,200 km2 with most areas being in Nepal (that is, 22,455 km2), followed by India (20,248 km2) and China (1,465 km2). Suitable tahr habitat occurs in Himachal Pradesh (8,903 km2), Uttarakhand (6,500 km2) and Sikkim (865 km2), and Jammu and Kashmir (3,979 km2).

The current global population of Himalayan Tahr in its native range (that is, China, India and Nepal) is difficult to estimate due to the paucity of data, but it may not exceed the size of introduced populations in New Zealand, South Africa, United States of America, and Argentina (likely extinct). No attempts to census tahr populations have been made from the other countries except from New Zealand. The total abundance of tahr in New Zealand alone, from 2016 to 2018, was placed between 24,777 and 47,461, with average density ranging from 0.06 to 9.2 tahr/km2.

Habitat and Ecology

Since Burrard’s (1925) hunting account, Himalayan Tahr has been known to traverse the steepest precipices. In general, they inhabit steep rocky mountain slopes, between 3,000–4,000 m asl, with woods and rhododendron Rhodondendron sp. scrub (Smith et al. 2008).

In Nepal, various surveys—like those in Kang Chu area (Schaller 1973), Everest National Park (Ale 2007), Langtang National Park (Green, 1979) and Annapurna Conservation Area (Gurung 1995)—reported that tahr occupy various habitat types from open alpine grassland and subalpine scrubland to sparse or even dense forests (tahr winter habitat). Precipitous cliffs break the continuity of these habitats. The best tahr habitat in the Everest region can be described as cliff faces broken by ledges supporting grasses, forbs and shrub mats at higher altitudes (mean 3,863 m, SE=0.9, range 3,260 m - 4,800 m, n=191) and patches of open pine or birch forest at lower altitude (mean 3,621 m, SE=1.4, range 3,300 m - 4,031 m, n=66). Tahr was reported from as high as 5,200 m (e.g., in Langtang: Fox 1974) and as low as 2,500 m in Kang Chu (Schaller 1977). In these mountains, steep hill slopes and undulating terrains are often characteristically interrupted by abrupt cliffs which act as oasis for these cliff-huggers whose presence is often predictive in these enclaves. This cliff-hugging behaviour of tahr restricts its own distribution (Ale 2007) and perhaps limits its group size as well.

Himalayan Tahr is diurnal, with varying group sizes depending on the degree of habitat ruggedness that characterizes particular localities. Group size of tahr is also influenced by the abundance of food and predation pressure. For instance, in Everest, group size ranged from 1-46 (average of ca. 8, n=277), during 2004 to 2006 (Lovari 1992, Ale 2007). The average group size increased over the decade in Everest perhaps in response to the return of snow leopards to the region (Ale 2007). Tahr formed comparatively larger groups in Annapurna Base Camp, Annapurna Conservation Area (13.8, range 1-57, n=134: Gurung 1995) and Langtang (average 15, largest group 77: Green 1979). Both Annapurna and Langtang lacked large predator, such as the snow leopard, in alpine and subalpine habitat, but most of these areas were characterized by undulating grasslands and scrublands thereby providing more plant forages for herbivores.

The prevalence of local hunting may also influence the average group size. In Himachal Pradesh, western Himalaya (India), group size was very small (ca. 1.7, n = 7) with severe hunting in the past (Gaston et al. 1983). This may have been reflected in the overall density reported from different study sites. In Everest, the tahr density was ca. 3.4/km2 (with no human hunting but presence of large predator). Gurung (1995) reported tahr at the density of 7.7/km2 from Annapurna, with no human hunting and no large predator. In the absence of local hunting or natural predation, food can be the principle factor liming the size of populations. In overall Langtang (with no large predator and no human hunting), Tiwari (2006) reported 8.72 tahr/km2 (8 herds, 218 individuals, in an area of 25 square kilometre). In the Langtang region of Langtang National Park, local density of tahr reached as high as 24/km2 (Green 1979: 170 in 7 km2), where tahr was neither hunted nor its habitat grazed by livestock. On the other hand, Yala region of Langtang National Park, with ten times more domestic sheep and eight times more cattle than Langtang region, reached low tahr density (6/km2). In the absence of hunting in parts of New Zealand, tahr attained densities of >30/km2 (Tustin and Challies, 1978). Female groups can reach very high densities in New Zealand, with groups of 100–150 commonly observed in areas that have not been hunted (D. Forsyth, unpubl. data). With regular hunting their population, however, maintained a density of ca. 5/km2 (Tustin and Challies 1978)

Mating occurs from October to January, with it peaking around the first half of December (Lovari, S., unpubl. data). One or occasionally two kids are born in June and July after a gestation of 180-242 days. The age at sexual maturity is 1.5 years, with captive animals living up to 22 years (Smith et al., 2008). Females have home ranges of about 2 km2 centred on rock bluffs. Males appear to be highly mobile, and outside of the rut are segregated from females (D. Forsyth, unpubl. data).

Himalayan Tahr is known to eat grass, herbs and some fruits. On Mt. Everest, tahr’s diets consisted typically of such grasses and sedges as Carex, Avena, Poa, Trisetum, Cyperaceae and Imperata. (Shrestha et al. 2002): overall, the diets were composed of 47% herbaceous plants and shrubs, 28% grasses and 25% sedges. This was similar to that Green (1979) reported for tahr in Langtang valley (38% herbaceous plants and shrubs, 34% grasses, 21% sedges, 4% ferns and 4% mosses). Green (1979) found in winter tahr supplemented its diet with small amounts of mosses and ferns, presumably because other food is less readily available. The diets of livestock and tahr were similar in the Everest region, but the proportion of woody plants (Rhododendron and Cotoneaster) was higher and that of grasses and sedges were lower in the diet of livestock than tahr.

| Habitats | Suitability | Major importance |

|---|---|---|

Threats

In New Zealand, there is occasional commercial harvesting of tahr for meat. There is a substantial recreational hunt of this species, and adult males (≥4.5 years old) are highly sought after as trophies by recreational and trophy hunters.

In Nepal’s only in one hunting reserve, Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Himalayan Tahr is harvested for trophy (blue sheep, Pseudois nayaur, were more sought after than Himalayan Tahr). The income thus generated has been used for conservation and local income generation activities (Karki and Thapa 2011). Two types of revenue have been generated through trophy hunting: the revenue collected by the Nepal’s government’s wildlife department, and money collected by local communities (although not substantiated on a legal basis, so monetary figures are not known: the charge to hunters may have varied from $533–1,333 for a Himalayan Tahr (Aryal et al. 2015). Locals used the money collected from tahr and blue sheep trophy-hunting for community development activities, for example, upgrading facilities of the local health post, constructing trails, and maintaining a bridge. Government revenue collected from 2007 to 2012 totalled $184,372, a portion of which went to conservation activities (Aryal et al. 2015).The major threats in China are uncontrolled hunting and deforestation. In India, Himalayan Tahr is hunted for meat, and there is apparently significant competition with livestock for summer grazing in some areas. Tahr possibly survive in small patches of steep, rugged forests around the sub-alpine zone, while much of its habitat is lost due to heavy pressure from local people and from developmental pressures. In Nepal, threats come from an expanding human population and accompanying increases in livestock, habitat loss, and poaching. As a result of these factors, tahr populations are becoming increasingly isolated. Besides threats related to anthropogenic activities, avalanches during winters with high snowfall also can be a significant mortality factor for tahr.

| title | scope | timing | score | severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Use trade

In New Zealand, there is occasional commercial harvesting of tahr for meat. There is a substantial recreational hunt of this species, and adult males (≥4.5 years old) are highly sought after as trophies by recreational and trophy hunters.

In Nepal’s only in one hunting reserve, Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, Himalayan Tahr is harvested for trophy (blue sheep, Pseudois nayaur, were more sought after than Himalayan Tahr). The income thus generated has been used for conservation and local income generation activities (Karki and Thapa 2011). Two types of revenue have been generated through trophy hunting: the revenue collected by the Nepal’s government’s wildlife department, and money collected by local communities (although not substantiated on a legal basis, so monetary figures are not known: the charge to hunters may have varied from $533–1,333 for a Himalayan Tahr (Aryal et al. 2015). Locals used the money collected from tahr and blue sheep trophy-hunting for community development activities, for example, upgrading facilities of the local health post, constructing trails, and maintaining a bridge. Government revenue collected from 2007 to 2012 totalled $184,372, a portion of which went to conservation activities (Aryal et al. 2015).Text summary

Himalayan Tahr is not listed under threatened category of CITES.

It is listed as Category I species in China. Conservation measures proposed for China included undertaking surveys to determine the species’ distribution and status in Qomolangma Nature Reserve (Hu et al. 2014). Qomolangma Nature Reserve started the snow leopard program in 2015 funded by Vanke Foundation. The program undertook a large-scale wildlife survey and subsequent conservation projects that included educating local communities about tahr and other wildlife.

In India, protected areas with Himalayan Tahr include: Jammu and Kashmir – Kishtwar National Park (locally threatened); Himachal Pradesh - Great Himalayan National Park (confirmed), and Daranghati (locally threatened), Gamgul Siahbehi, Kanawar, Khokhan, Kugti, Manali (locally threatened or extinct), Rupi Bhaba, Sechu Tuan Nala, Tirthan and Tundah (locally threatened) Wildlife Sanctuaries; Uttarakhand -Nanda Devi and (probably) Valley of Flowers National Parks, Govind Pashu Vihar and Kedarnath Wildlife Sanctuaries; and Sikkim - Khangchendzonga National Park (Gaston et al. 1981, 1983, Green 1987; Kathayat and Mathur 2002). Tahr uses rugged forested slopes with temperate oak and pine forests, well below the subalpine areas where it is often currently located. This suggests that its current range distribution may reflect displacement from formerly used lower elevation areas. Conservation measures proposed for India include: 1) extend the Great Himalayan National Park as proposed, 2) establish the proposed Srikhand National Park (Himachal Pradesh), 3) devise innovative community based reserves for the species outside protected areas (these need to include community based protection, tourism, awareness, etc.), and 4) include areas with tahr in the innovative, participatory, landscape level planning and action under the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, Project Snow Leopard. Overall, the country’s conservation strategy clearly states conserving species in and outside protected areas.

A significant proportion of Nepal’s tahr occurs within protected areas, but its population is widespread in areas outside of protected areas (e.g., the region that lies between Manaslu and Langtang, Bhimthang valley between Manalsu and Annapurna, and Dolpo, Jumla, Mugu and Humla districts). The species occurs in all mountain protected areas of Nepal: Langtang, Rara, Sagamartha (Everest), Makalu-Barun and Shey-Phoksundo National Parks; Api Nampa, Annapurna, Manalsu, Gaurishankar and Kanchanjunga Conservation Areas, Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve, and Khaptad National Park.

Conservation measures proposed for Nepal: 1) maintain the current, closely controlled, legal hunting program in Dhorpatan, 2) consider a regulated program of low-level subsistence hunting by local villagers, and 3) undertake surveys to understand the increasing fragmentation of tahr populations and offer mitigation measures. The first steps to address this issue would be to begin in selected areas by mapping tahr habitat features such as cliffs (using 1:50,000 topographic maps), followed by ground surveys to validate the species’ presence/absence.

Dhorpatan Hunting Reserve is the only reserve in Nepal that allows trophy hunting of Himalayan Tahr along with blue sheep. From 2008 to 2011, Karki and Thapa (2011) reported 34 Himalayan Tahr were harvested: 18 in 2008/09 (100% harvest; quota set by the government), 11 (61% in 2009/10) and 5 (28 % in 2010/11). A quick glance on the numbers harvested indicates they were not so small numbers if adult males have been the only target. It would mean some 10-15 % of the adult male (trophy) population (Sandro Lovari, pers. comm). Perhaps the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation – Nepal should consider revaluating the trophy hunting of tahr on a sustainable basis.